- Topic1/3

21k Popularity

36k Popularity

680 Popularity

177 Popularity

47 Popularity

- Pin

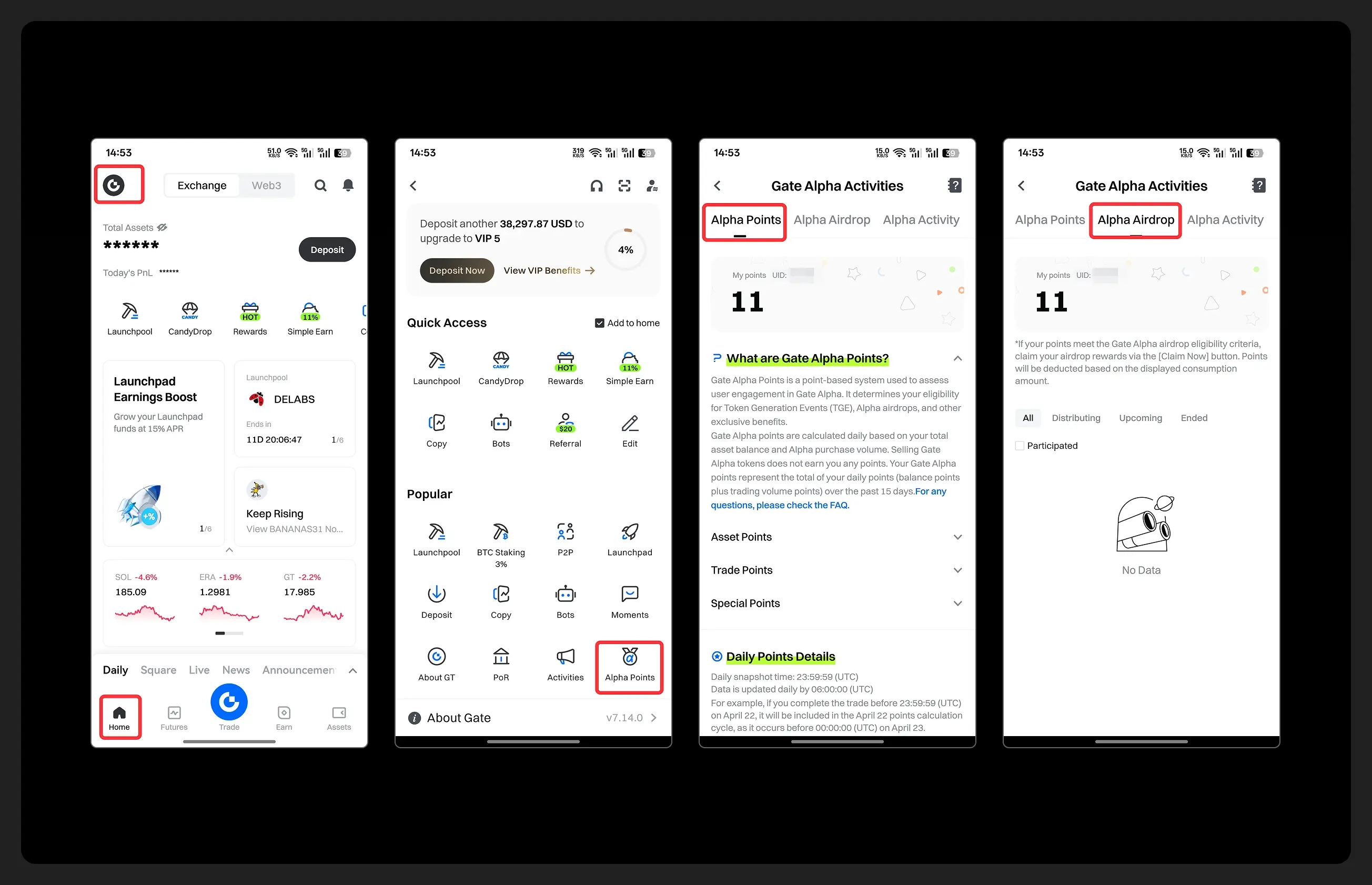

- Hey fam—did you join yesterday’s [Show Your Alpha Points] event? Still not sure how to post your screenshot? No worries, here’s a super easy guide to help you win your share of the $200 mystery box prize!

📸 posting guide:

1️⃣ Open app and tap your [Avatar] on the homepage

2️⃣ Go to [Alpha Points] in the sidebar

3️⃣ You’ll see your latest points and airdrop status on this page!

👇 Step-by-step images attached—save it for later so you can post anytime!

🎁 Post your screenshot now with #ShowMyAlphaPoints# for a chance to win a share of $200 in prizes!

⚡ Airdrop reminder: Gate Alpha ES airdrop is

- Gate Futures Trading Incentive Program is Live! Zero Barries to Share 50,000 ERA

Start trading and earn rewards — the more you trade, the more you earn!

New users enjoy a 20% bonus!

Join now:https://www.gate.com/campaigns/1692?pid=X&ch=NGhnNGTf

Event details: https://www.gate.com/announcements/article/46429

- Hey Square fam! How many Alpha points have you racked up lately?

Did you get your airdrop? We’ve also got extra perks for you on Gate Square!

🎁 Show off your Alpha points gains, and you’ll get a shot at a $200U Mystery Box reward!

🥇 1 user with the highest points screenshot → $100U Mystery Box

✨ Top 5 sharers with quality posts → $20U Mystery Box each

📍【How to Join】

1️⃣ Make a post with the hashtag #ShowMyAlphaPoints#

2️⃣ Share a screenshot of your Alpha points, plus a one-liner: “I earned ____ with Gate Alpha. So worth it!”

👉 Bonus: Share your tips for earning points, redemption experienc

- 🎉 The #CandyDrop Futures Challenge is live — join now to share a 6 BTC prize pool!

📢 Post your futures trading experience on Gate Square with the event hashtag — $25 × 20 rewards are waiting!

🎁 $500 in futures trial vouchers up for grabs — 20 standout posts will win!

📅 Event Period: August 1, 2025, 15:00 – August 15, 2025, 19:00 (UTC+8)

👉 Event Link: https://www.gate.com/candy-drop/detail/BTC-98

Dare to trade. Dare to win.

$380 million targeted? Analyzing the legal principles and pathways for Chinese creditors' rights protection from FTX's motion.

Author: Gui Ruofei Lucius

"The judicial experience from the Mt. Gox and Celsius cases has provided favorable references and practical endorsements for Chinese creditors in the FTX case to pursue their claims. Although the current motion path for FTX tends to be closed and exclusive, there is still discretion in the bankruptcy court. As long as Chinese creditors act appropriately, there is still hope to achieve rights confirmation and compensation."

On July 2, 2025, the FTX Recovery Trust submitted a motion titled "Motion to Implement Restricted Procedures in Potentially Restricted Jurisdictions" to the U.S. Bankruptcy Court in Delaware, requesting the establishment of a differentiated compensation mechanism for creditors in 49 jurisdictions, including China. The core content of the motion can be summarized as follows: if the local attorney engaged by the trust determines that payment to a certain jurisdiction would violate local cryptocurrency regulatory laws, then the creditors' claims in that region will be classified as "disputed claims," which may ultimately result in the complete loss of their right to compensation, and the claims will be taken over by the FTX Recovery Trust.

According to relevant statistics, Chinese creditors hold $380 million in claims, accounting for about 82% of the total claims in restricted areas. This motion has also attracted widespread attention in the Web3 field and the legal practice of the cryptocurrency industry, not only because it relates to the claims rights of hundreds of thousands of Chinese investors, but also because it may have far-reaching implications for the legal applicability, user protection boundaries, and compliance paths of global cryptocurrency companies in future cross-border bankruptcies.

This article intends to analyze the issues involved in the motion and the current situation of Chinese creditors' rights protection from three dimensions: the motion system, the application of law, and case analysis.

I. Introduction to the Motion System and Brief Analysis of the Content of This Case's Motion

Before analyzing the relevant disputes regarding the motion, it is necessary to first introduce the basic mechanism of the "Motion Practice" in the U.S. bankruptcy process. A motion under U.S. bankruptcy law refers to a formal request submitted to the bankruptcy court by the debtor, creditor, or other interested parties concerning specific procedural matters or entities. Its legal basis is usually found in the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure, supplemented by specific local court rules for enforcement.

In Chapter 11 of the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure, motions can cover a wide range of issues, from asset disposal, creditor confirmation, priority of claims, to the denial of creditor eligibility for recovery as illustrated in this case, all of which can be initiated through the motion process. Motions typically require the submission of a formal written document (Motion Brief) that outlines the legal basis and factual assertions, and relevant evidence must be provided to support it. For motions involving significant procedural rights, bankruptcy courts usually schedule a hearing to listen to the opinions of relevant parties, review whether the procedures comply, and whether the assertions in the motion are valid before making a judgment. In other words, the motion system constitutes an important part of the U.S. bankruptcy process and is also a crucial tool for bankruptcy participants to advance their own interests.

Returning to the case, the FTX bankruptcy trust invokes Section 105 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code (the court has the power to issue necessary orders), Section 114 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code (authorization for the implementation of reorganization plans), and Rule 302 of the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure, requesting the court to authorize the trust to execute "Restricted Jurisdiction Procedures." The motion asserts the rejection of payments to the 49 declared creditors in the motion's Attachment B from "potential restricted jurisdictions," including countries such as China, Russia, Egypt, and Nigeria. The FTX bankruptcy trust provides reasoning in the motion that the cryptocurrency regulatory policies in the aforementioned jurisdictions may lead to relevant fines or penalties, hindering the legitimacy of the debtor's payments while potentially exposing relevant personnel to criminal risks.

(The above image is part of the original text of the motion proposed by the FTX bankruptcy trust, explaining the main reasons for the motion.)

The substantive issue raised by this motion lies not only in whether U.S. law permits the exclusion of specific creditors' rights to compensation, but also in whether the court has the authority to deny the claims of creditors from "restricted countries," which involves complex disputes at multiple levels. The following analysis will be conducted in detail from both the substantive law and procedural law perspectives.

II. Scope of Legal Application and Disputes: Procedure and Substance

From the perspective of substantive law, the core defense reason cited in the motion by the FTX bankruptcy trust in this case is that "paying users in restricted jurisdictions may violate local cryptocurrency and foreign exchange control regulations." This assertion superficially falls within the category of the bankruptcy administrator's "compliance risk management," but in essence, it has at least two obvious flaws in terms of legal application and interpretation:

Firstly, the motion proposed by the FTX bankruptcy administrator confuses the nature of payment instruments and compensation assets. The objects FTX intends to use for compensation are not cryptocurrencies, but rather US dollars or court-approved stablecoins (such as USDC, USDP, etc.), and such payment methods are not directly restricted within the international payment system. Similar successes can be seen in the bankruptcy liquidation cases of Celsius and Mt.Gox, where the bankruptcy administrators of both cases, under court supervision, paid compensation to individual creditors located in restricted jurisdictions (such as China and Russia) through SWIFT international wire transfers or stablecoin transfers. The courts in those jurisdictions did not raise compliance exemption requirements regarding the payment actions themselves, nor did it trigger any related regulatory disputes.

Secondly, the motion misinterprets the immediate applicability of Chinese laws and administrative regulations. Under the current legal framework in China, there is no comprehensive prohibition directly against individuals holding cryptocurrency assets or receiving payments in cryptocurrency from abroad. The notice issued on September 4, 2017, by the central bank and seven ministries, titled "Notice on Preventing the Risks of Token Issuance and Financing," focuses on restricting financial institutions from participating in token issuance and trading with ICO platforms; while the notice issued in September 2021 by the People's Bank of China and ten ministries, titled "Notice on Further Preventing and Handling the Risks of Virtual Currency Trading Speculation," although it further strengthens the crackdown on trading platforms, does not negate the legality of individuals passively receiving or holding cryptocurrency assets. More importantly, civil courts in multiple regions have recognized in some judicial practices that cryptocurrency assets (such as BTC, USDT, etc.) possess the status of "network virtual property," applicable under Article 127 of the Civil Code for protection, and can be protected as objects of debt enforcement, which is also true in the criminal field. Therefore, the interpretation of this motion regarding China's regulatory policy lacks universal binding force and diverges from the development trend of practical case law.

From the perspective of procedural law, there are still many aspects of the procedural arrangements proposed by the FTX bankruptcy trust that are open to discussion.

Although FTX's motion formally follows the procedural rules of the U.S. bankruptcy court, it essentially introduces a compliance review mechanism that is led by itself and relatively closed in operation. Specifically, the FTX bankruptcy trustee unilaterally hires lawyers to issue legal opinions on whether specific jurisdictional compliance risks are compensable (Legal Opinion), and requires that such opinions must be "unqualified and unconditional" (Unqualified Legal Opinion) in order to be accepted. Once a lawyer in a particular country or region believes that payment may have legal obstacles or cannot issue an absolute unqualified opinion, all claims in that region will automatically be classified as "disputed claims" (Disputed Claims), suspending payments or even completely depriving claimants of their qualification to claim. This review mechanism is particularly likely to cause substantive injustice in regions with regulatory ambiguity or opaque policies (such as China). For instance, in China, where there are currently no clear laws prohibiting individuals from receiving U.S. dollar settlement payments or holding stablecoins, local lawyers, based on the factor of "risk cannot be assessed," also find it difficult to issue absolute affirmative legal opinions. In practice, most lawyers, even if they subjectively tend to believe that compliance risks are limited, will still include reservation clauses in their opinions based on their professional duty of caution, resulting in "unacceptable opinions" (Unacceptable Opinion) becoming the procedural default.

The more serious problem is that this compliance review mechanism is not established and promoted by a neutral court, but is entirely controlled by the FTX bankruptcy trust. From the selection of lawyers, issuance of instructions, to the setting, interpretation, and application of the legal opinions, everything is unilaterally controlled by the debtor. This review mechanism of "pre-setting conclusions and then issuing legal opinions for demonstration" has a sense of "shooting first and drawing the target later." Furthermore, this procedural design has not undergone a substantive review process by the court itself. If the court directly accepts the motion request solely based on the content of the legal opinions submitted by the debtor, it effectively transfers the decision-making power regarding the claims of certain national creditors to the legal advisors controlled by the debtor. This procedural design is contrary to the core principle of "fair treatment of similar creditors" emphasized by U.S. bankruptcy law, and will also place creditors from specific jurisdictions like China in a systematically disadvantaged position.

In addition, the jurisdictional issues discussed in this article are also controversial. As a territorial court, the U.S. bankruptcy court generally has jurisdiction limited to U.S. bankruptcy debtors and their assets, but FTX's customer base is characterized by a high degree of globalization, and its platform's creditor composition is not solely governed by U.S. law, containing complex elements of transnational contract law. Although most Chinese creditors opened accounts through the FTX international platform, they did not explicitly agree to the application of U.S. law or submit to the exclusive jurisdiction of U.S. courts. Therefore, whether a single jurisdiction's court can wholly exclude the claims of users from specific countries based on policy factors remains a legal controversy. According to the general principles of private international law, while bankruptcy proceedings have a concentrated liquidation effect, they should not arbitrarily deprive foreign creditors of their legitimate rights to claim, otherwise it may violate the spirit of international laws such as the Hague Convention on Choice of Court Agreements and the UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency. If U.S. courts use "compliance risk" as a universally applicable basis for motions, it may set a precedent for other debtors in future cross-border bankruptcy cases, further weakening the legal status of foreign creditors.

III. Horizontal Comparative Study of Similar Cases

The FTX case is not the first time the cryptocurrency industry has faced cross-border debt settlement disputes arising from the bankruptcy of a large platform. From past experiences, the Japanese Mt. Gox case and the American Celsius case can serve as typical comparisons for this case. Although the two cases belong to different legal jurisdictions and have different regulatory attitudes, they share common characteristics involving large-scale cross-border creditors, substantial cryptocurrency asset liquidation, and significant impacts on the rights of Chinese users. The court's handling paths, the role of trustees, and the principles of settlement in these cases constitute important references for analogical analysis of the FTX case.

(1) Mt. Gox case

Mt. Gox is one of the most representative bankruptcy cases in the history of Bitcoin. In 2014, Mt. Gox announced bankruptcy due to a trading system vulnerability and a massive theft of BTC, with over 20,000 creditors distributed globally, among which Chinese creditors accounted for a significant proportion. The case is under the jurisdiction of the Tokyo District Court in Japan and is subject to the Japanese Bankruptcy Law and the subsequently initiated Civil Rehabilitation Procedures. In terms of program design, the court did not set any restrictive thresholds based on the nationality of users or regulatory risks, but instead unified the collection of global creditor claims through the "Creditor Portal System," supporting multilingual interfaces including Chinese and English, further reducing procedural barriers.

More importantly, the Japanese court has required the trustee to propose a "proportional compensation + return of remaining assets in BTC" plan based on the actual structure of the assets, without distinguishing whether the creditor's country of origin has a conservative regulatory stance on virtual currencies. For example, in China, although the "Announcement on Preventing the Risks of Token Issuance and Financing" had been issued at that time, it did not affect the claims review and compensation process for Chinese users. The entire process, under the leadership of the Tokyo District Court, maintained a high degree of judicial neutrality and transparency, and the trustee regularly published multilingual progress announcements and responded to collective objections. Ultimately, the vast majority of creditors were able to receive compensation through methods such as JPY, wire transfer, or BTC. The Mt. Gox bankruptcy case illustrates that even in a complex cross-border context, as long as the court leads the process fairly and applies a unified compensation standard, the regulatory complexity of crypto assets does not constitute a sufficient reason to prohibit or restrict external creditors' compensation.

(2) Celsius Case

Celsius Network, one of the largest crypto lending platforms in the United States, filed for bankruptcy reorganization in 2022, which is being handled by the Southern District of New York Bankruptcy Court, under Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code. In this case, Celsius, like FTX, faces a large number of cross-border creditors, particularly with a wide user base in Asia, Europe, and other regions.

In terms of specific procedural arrangements, the bankruptcy court has established a creditor portal system with the liquidation company (Celsius Creditor Recovery Corporation), which opens the creditor declaration to the world. The system supports multilingual operations and allows creditors to choose their own payment methods, including US dollar stablecoins or equivalent Bitcoin and Ethereum. It is noteworthy that the Celsius case did not attempt to exclude any specific country's creditors through a motion nor establish a "restricted jurisdiction" list. For Chinese users in the Celsius case, although the Chinese government has very strict regulatory policies on virtual currencies, the Southern District Court of New York did not adopt "potential compliance obstacles" or "foreign exchange controls" as the basis for excluding or freezing the repayment rights of Chinese creditors.

More importantly, the court upheld the fundamental principle of equal treatment of creditors under bankruptcy law in its ruling, and clearly stated that unless there is a clear legal prohibition or a request for assistance from a foreign court, foreign creditors' rights should not be unilaterally denied due to regulatory ambiguity. In fact, creditors, including a large number of users from mainland China in the Celsius case, completed initial compensation in early 2024, most of whom verified their identities through third-party KYC verification platforms and received USDC transfers or corresponding BTC allocations. This also demonstrates the court's insistence on a dual-track processing logic of substantive review and procedural guarantees.

The cases of Mt. Gox and Celsius demonstrate that in bankruptcy handling mechanisms with strong judicial leadership and transparent procedural rules, courts tend to uphold the basic civil rights of creditors, even when the country of the creditors has ambiguous regulations on crypto assets or foreign exchange restrictions. The principle of "non-discriminatory participation" is advocated, which has important reference value for Chinese creditors in their rights protection path in the FTX case.

First, from the perspective of judicial philosophy, both the Japanese court's opening of a declaration channel for Chinese creditors and support for local currency compensation options in the Mt. Gox case, and the New York bankruptcy court's explicit refusal to deny the qualification of Chinese creditor claims in the Celsius case based on "regulatory uncertainty" demonstrate that modern courts are paying more attention to substantive review and the protection of creditors' equal participation rights when handling cross-border cryptocurrency bankruptcy cases. In particular, in the Celsius case, the U.S. court did not cite any country's regulations to exclude compensation for users from mainland China and other regions, but instead achieved a balance between risk control and compliance through procedural tools such as KYC and identity verification.

Secondly, from the perspective of the bankruptcy court's discretionary mechanism, although the U.S. bankruptcy process grants debtors certain motion rights and procedural design space, it ultimately requires the bankruptcy court to conduct a substantive review of the motions. Considering the current procedural direction of the FTX case — including the opposition opinions submitted by Chinese creditor representatives and the widespread protests from the global creditor community — it can be reasonably expected that the court may not unconditionally adopt the FTX bankruptcy trust's motion to "exclude creditors from restricted jurisdictions," and may lean towards a more detailed adjudication approach that addresses regions separately. In this context, if Chinese creditors can organize collective action through legal representatives, formally submit opposition motions, and actively participate in the hearing process, there remains hope for their claims to be recognized and compensated by the court.

Of course, the final outcome of the rights protection ultimately depends on how the court balances the conflicts between "compliance barriers" and "procedural equality," as well as "certain creditors" and "all creditors." Once the court adopts the logic of FTX's motion, Chinese creditors may need to further appeal or seek to amend the process through diplomatic channels.

In summary, the judicial experience from the Mt. Gox and Celsius cases has provided a favorable reference and practical endorsement for Chinese creditors in their pursuit of compensation rights in the FTX case. Although the current path of FTX motions tends to be closed and exclusive, there is still discretion in bankruptcy court, and as long as Chinese creditors act appropriately, there remains hope for the confirmation of rights and the realization of compensation.